| Location: | Balashi/Frenchman’s Pass |

| Year Built: | 1899 |

| Monument status: | Protected |

| Ownership: | Government of Aruba |

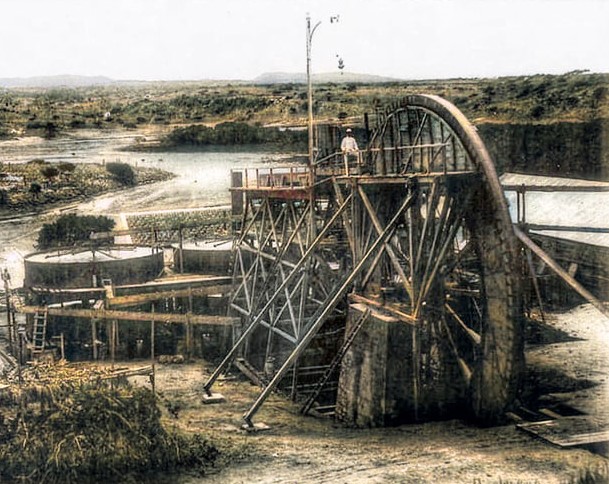

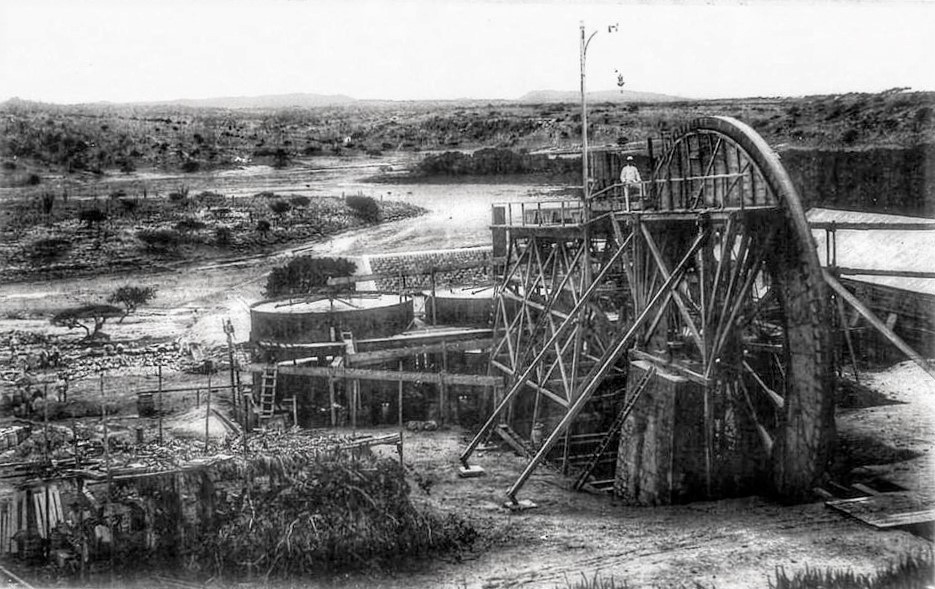

Balashi Gold Smelter * 1899

Category: Other Districts

The first gold mining industry was located at the Bushiribana Gold Smelter, where the Aruba Gold Mining Company was active till 1899.

In that year, the company was dissolved and a new one was founded in London, the Aruba Gold Concessions, Ltd. Under the leadership of Messrs. Jennings and Hopkins, this company built the gold smelter at Balashi, between the Spanish Lagoon and the Frenchman’s Pass.

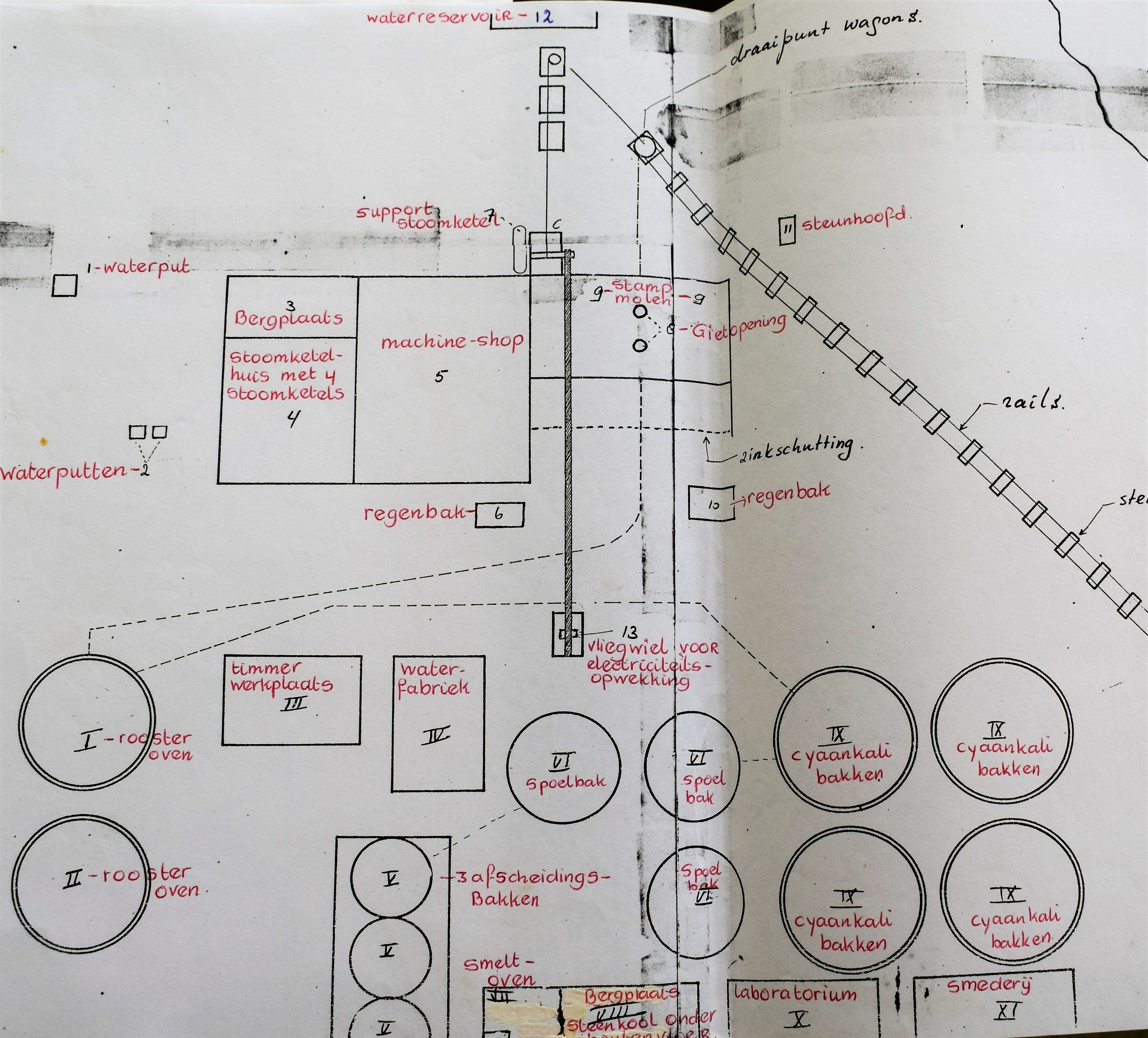

To supply the materials for the construction of the smelter, a pier was constructed in Spanish Lagoon, from where the material was transported to the construction site by rail wagon – without a locomotive.

Also on the advice of Jennings and Hopkins, the ‘Miralamar’ mining area, the most productive on the island, was further developed. From there the gold-bearing rock obtained from the mine was transported to Balashi by a locomotive-like machine with trailers behind it. It was called ‘Traction Engine’ by the English, corrupted by the locals to ‘Trekinchi’. It drove on the specially constructed road leading from Jamanota via Bringamosa and the Frenchman’s Pass to the Balashi gold smelter.

The ‘Trekinchi’ was the first motorized vehicle in Aruba, it ran on steam, was extremely loud, and super slow, but attracted a lot of attention.

The Balashi smelter was very modern – for those days -, with 6 fire furnaces, a high crushing mill, a melting furnace and huge purification vats. The material was brought from the crushing plant to the purification tanks via narrow railway tracks on high wooden bridges.

The Aruba Gold Concessions had their own pier in the harbor of Oranjestad.

Due to the enormous investments required for business operations and the low returns from gold mining, the Aruba Gold Concessions has never been able to operate profitably, except for one year.

After eight years, activities were discontinued again in 1908. A local company, the Aruba Goud Maatschappij, took over the concession plus the machinery and buildings. Initially the results were quite good and the Gold Company was the main source of income for the island. But during the First World War, dynamite and the raw materials to purify the ores were no longer available and production came to a complete standstill.

After the war, the machines at Balashi, which had not been operated for years and had not been maintained, were no longer usable. This put an end to gold mining in Aruba. The dilapidated ruins of Balashi, along with those of Bushiribana, are what remains of what seemed to be a promising industry for the island. You can find more about this in the Museum of Industry in the restored water tower in San Nicolas.

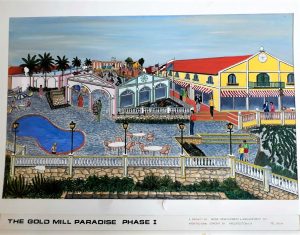

The Balashi Gold Mill Paradise.

In 1985, the Balashi gold smelter was in the news again when about 30 former oil workers from the Lago refinery took the initiative to start a tourism project there.

That year it was announced that the Lago was closing and employees who were (almost) ready for retirement could be dismissed with an interesting bonus. They wanted to invest these amounts in a project that would contribute to the further development of tourism on the island after the closure of the Lago and when the Status Aparte came into effect in 1986.

The Balashi Gold Mill Paradise project was budgeted at 1.2 million florins and was to include a natural park with a combination of cultural, historical and tourist attractions. A large building, intended as a restaurant or casino, was built at the top of the hill behind the ruins of the gold smelter. But the project was not completed.

When the Aruba Development Bank, which managed the project’s funds, collapsed, the former Lago employees lost the invested pension premiums. What now remains is the unfinished building that has fallen into disrepair, covered in graffiti.

It has a magnificent view over the gold ruins, the plain behind the Spanish Lagoon and the hills of Parke Nacional Arikok.

Walking paths and a staircase made of natural stone have been constructed through the ruins. The ruins themselves have never been restored, but the complex has been given the seal of a protected monument by the Aruba Monuments Bureau.